The Star-Spangled banner – from Sudbury

The Star-Spangled banner – from Sudbury

Next time you walk down Cross Street towards Ballingdon have a look at the cottages on your right - specifically numbers 75-78. They might look fairly nondescript now - modest terraced houses - but they have a hidden history that is valued more across the Atlantic than here. It was here that bunting was made. Bunting? Yes, both large and small flags much used in the Navy. The small sort could be assembled to make a message such as that at the battle of Trafalgar “England expects every man will do his duty”. But what has that got to do with America?

The house on the right and the next three cottages (75-78 Cross Street) belonged to Abraham Griggs, a say maker, from 1695. He also used the premises for making bunting for the Royal Navy and for export, including the US, and it was here that the fabric for the Stars and Stripes was made in 1813.

To step back in time a little: the demand for heavy woollen broadcloth such as had been woven in Sudbury declined in the 16th/17th centuries and so weavers turned to lighter-weight fabric such as bays, says, crepes and bunting. The latter became a branch of the textile industry almost unique to Sudbury and, because of its lighter weight, was mainly woven by women.

What exactly is bunting - or as it was known at the time - buntine? Described in 1826 as: “a thin sort of woollen stuff, very pliable though strong; it is wove in strips, blue, white, red, etc. which strips are afterwards sewed together, into the form needed for the specific flag.” Being loosely woven its edges were tightly double-hemmed (by hand) for strength and to prevent them unravelling in the wind.

In 1814 Britain was at war (again – the War of 1812) with the newly established United States of America. Fort McHenry near Baltimore had no Stars and Stripes flag and so one was ordered. Living in Baltimore was fervent patriot Mary Pickersgill, a flag-maker (yes, really!) and she was commissioned to produce a 30 x 42-feet garrison flag for the fort. This was a massive undertaking. Much bunting had to be acquired and even though Britain was at war with the US, cargo ships arrived in American ports, some of them carrying bunting from Sudbury.

Mary calculated how much bunting would be needed in red, white and blue. Bunting was woven in 18-inch wide strips. The red and white stripes of the American flag needed to be 2 feet wide so this required careful cutting and sewing by Mary’s patriotic female relatives who worked on the flag mostly for no pay. The blue section was also made up of sewn-together strips of 18-inch bunting. The white stars were cotton fabric (possibly also woven in England.)

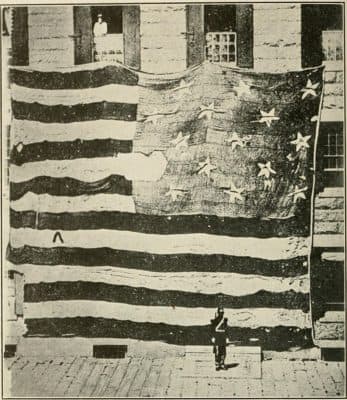

The flag that flew over Fort McHenry in 1814, photographed in 1873 in the Boston Navy Yard.

After about six weeks, the flag was assembled and taken to Fort McHenry. It was flying over the fort when 5,000 British soldiers and 19 Royal Navy ships attacked Baltimore on 13 September 1814. The firing went on until nightfall. Was it still there the following morning? (“Oh, say, can you see by the dawn’s early light…?”) It was! Fort McHenry had resisted the British bombardment (“Whose broad stripes and bright stars, through the perilous fight…”)

“The ‘Sudbury’ Stars and Stripes’ flying over Fort McHenry during the bombardment by the British. Painting ‘The Bombardment of Fort McHenry’ by Alfred J. Miller.

The war (which some regarded as America’s Second War of Independence) ended in February 1815. (We lost - again.)

It is, therefore, somewhat ironic that the Stars and Stripes which flew over that Baltimore fort in defiance of the British and was the inspiration for the American national anthem, had begun life in Cross Street, Sudbury.

Anne Grimshaw

Sally Johnston. Mary Young Pickersgill Flag Maker of the Star-Spangled Banner, 2014

Isaac Taylor. Scenes of Wealth or Views and Illustrations of Trades, Manufactures, Produce and Commerce, 1826

Barry Wall. Sudbury, 2004

National Anthem of the USA:

“Oh! say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars, through the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof thro’ the night that our flag was still there.

Oh! say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave,

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

Sung to the tune of an old English drinking song, ‘The Anacreontic Song’, the official song of the Anacreontic Society, an 18th-century gentlemen's club of amateur musicians in London. (Sorry, can’t find a Sudbury connection with that – but maybe Gainsborough was a member of it!)

The original Star-Spangled Banner, the flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the song that would become the national anthem of the USA, is among the most treasured artefacts in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

A Mackman Group collaboration - market research by Mackman Research | website design by Mackman